Hemoglobinuria is a rare but serious condition that may silently signal underlying health issues. It is is the presence of free hemoglobin in urine, which can damage organs, cause disabling fatigue, and threaten life. Understanding the early clues that the disease could be taking hold is crucial. Herein we’ll outline the signs and more about the disease.

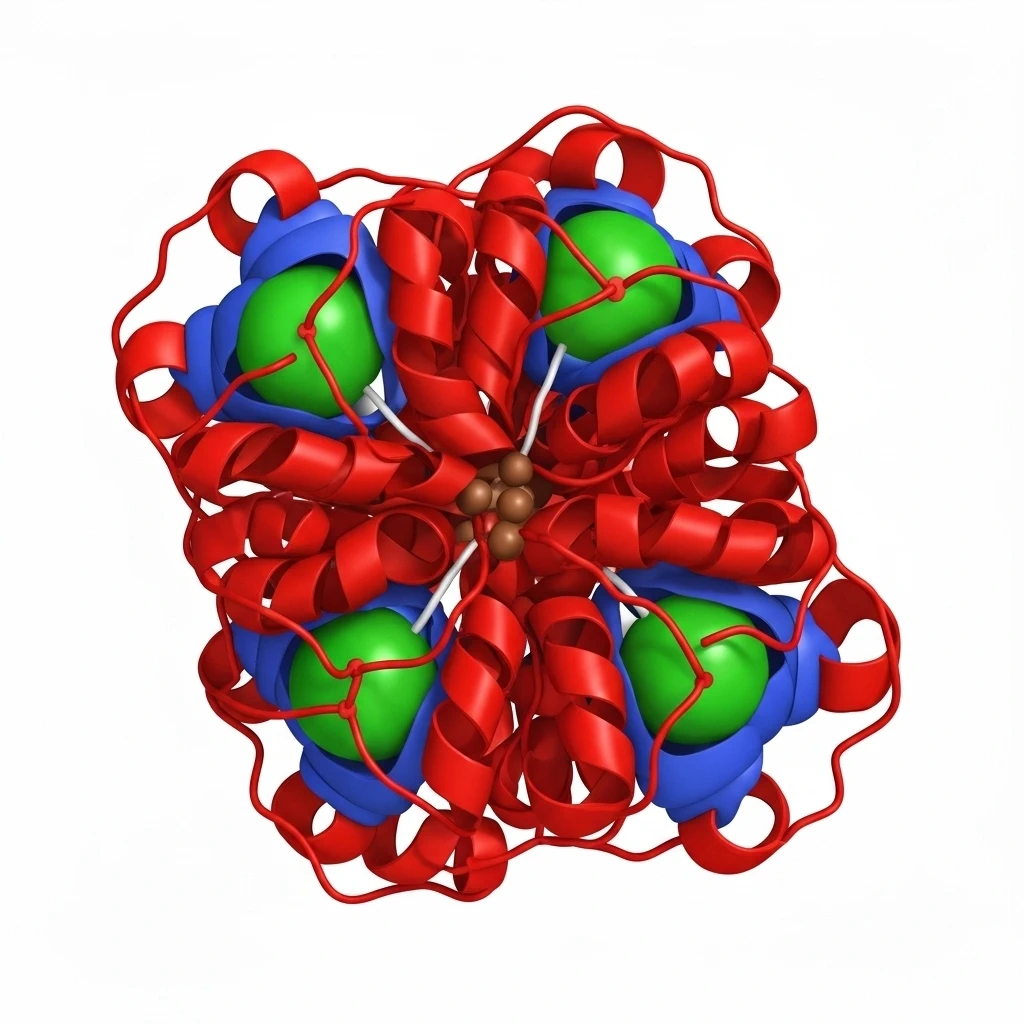

Hemoglobinuria is the presence of free hemoglobin in urine, most famously associated with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH)—a rare, acquired blood disorder in which red blood cells are destroyed by the body’s own complement system. In PNH, a mutation in the bone-marrow stem cell gene PIGA leads to loss of protective, GPI-anchored proteins on blood cells (notably CD55 and CD59). Without these shields, complement punches holes in red cells, releasing hemoglobin that can darken the urine and strain the kidneys. Although “nocturnal” is in the name, hemolysis can occur at any time; nighttime concentration of urine simply makes the discoloration easier to notice in the morning. Left unrecognized, the disease can damage organs, cause disabling fatigue, and lead to life-threatening blood clots. (Cleveland Clinic)

The root cause is not inherited but acquired: a somatic mutation in the PIGA gene arises in a hematopoietic stem cell, and its progeny—red cells, white cells, and platelets—lack GPI-anchored complement regulators. This vulnerability drives chronic intravascular hemolysis and also contributes to a striking tendency toward thrombosis, especially in unusual veins such as hepatic (Budd–Chiari syndrome) and abdominal sites. PNH frequently overlaps with bone-marrow failure syndromes like aplastic anemia and myelodysplastic changes, which can amplify anemia and infection risk. Triggers for hemolytic flares include infections, surgery, and pregnancy, reflecting how inflammation can intensify complement activity. (MedlinePlus Genetics)

The list of signs of the disease are numerous. Early clues often begin with the urine. Patients describe cola- or tea-colored urine on waking, which may fade during the day as dilution increases. That discoloration can come and go, aligning with bursts of hemolysis. Alongside the urinary changes, the list of signs includes profound fatigue, pallor, shortness of breath on exertion, and rapid heartbeat from anemia. Smooth-muscle symptoms—abdominal pain, chest or back pain, trouble swallowing, and, in men, erectile dysfunction—reflect nitric oxide depletion by free hemoglobin. Headaches, jaundice, dark stools from hemolysis, and recurrent infections or easy bruising (when marrow failure is present) round out the symptom picture. Any combination of dark morning urine, unexplained anemia, abdominal pain, and clotting symptoms warrants prompt evaluation. (AAMDSIF)

Because hemoglobinuria itself is a sign rather than a diagnosis, confirmation rests on blood tests that demonstrate complement-sensitive cells. The gold standard is flow cytometry, which looks for loss of GPI-anchored proteins (such as CD55/CD59) on red and white blood cells; a reagent called FLAER directly identifies GPI-anchored structures on granulocytes with high sensitivity. Lab evidence of active hemolysis—elevated LDH, low haptoglobin, elevated indirect bilirubin, and reticulocytosis—is common, and kidney studies may show hemoglobin-related injury if hemolysis has been brisk or prolonged. Clinicians also evaluate for marrow failure with counts and, when indicated, marrow biopsy, because PNH frequently coexists with aplastic anemia. (Johns Hopkins)

Untreated hemolysis can injure kidneys, drive gallstone formation, and, most critically, provoke thrombosis—the leading cause of death in PNH—so modern care aims to block complement and stabilize the marrow. C5 inhibitors such as eculizumab and the long-acting ravulizumab prevent formation of the membrane attack complex, sharply reducing intravascular hemolysis, transfusion needs, pain crises, and thrombotic events. A proximal complement inhibitor that targets C3 can also reduce hemolysis and improve anemia in selected patients, especially when extravascular hemolysis persists. Because complement blockade increases susceptibility to certain meningococcal infections, up-to-date vaccination and, in some cases, prophylactic antibiotics are essential parts of the plan. (Cleveland Clinic)

Supportive measures remain important. Transfusions may be needed during severe anemia, with iron and folate supplementation to replace losses from chronic hemolysis. Anticoagulation is considered for patients with clots or very high thrombotic risk, balanced against bleeding concerns when platelets are low. Pain control, hydration, and prompt treatment of intercurrent infections help blunt hemolytic triggers. For patients whose main problem is marrow failure rather than hemolysis, immunosuppressive therapy can improve counts. Allogeneic stem-cell transplantation is the only curative option but carries significant risks; it is generally reserved for severe marrow failure or refractory, high-risk disease after careful specialist evaluation.

Living with PNH means learning personal warning signs and building a routine that reduces crises. Patients track hemoglobin and LDH trends, watch for new headaches, abdominal pain, chest discomfort, or leg swelling that could herald a clot, and seek care quickly for fevers or infections that may ignite hemolysis. Many people, once on effective complement therapy and a vaccination schedule, return to work and daily life with fewer hospital visits and far less fatigue. Pregnant patients require coordinated care among hematology, obstetrics, and anesthesia teams, since pregnancy increases both hemolysis and clotting risk but can be managed successfully with modern therapy.

Not every episode of dark urine is PNH; exercise-induced hemoglobinuria and hematuria from kidney or urinary causes are on the differential. Still, the combination of recurrent dark morning urine, anemia-related fatigue, smooth-muscle pains, and any thrombotic symptoms should prompt specific testing rather than watchful waiting. Early recognition allows timely complement inhibition, reduces kidney and clotting complications, and changes the trajectory from a dangerous, unpredictable disorder to a manageable chronic disease with improving long-term outcomes.

Clarity-Spot is for informational purposes only. It is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on Clarity-Spot.